Keeper Of His Own Animal Kingdom John Hiltunen, who has diabetes and dyslexia, never made art at all until he was 54. Now his weird and wild collages are the toast of the art world.

By Carey Dunne July 7, 2017

Wearing starred-and-striped suspenders over a white t-shirt, artist John Hiltunen points to a small chest of drawers next to his workspace, housed in a cavernous former auto-repair shop in downtown Oakland, California: “Bodies go in this drawer; heads go in this one,” he says. Piled on his desk are glossy magazines—Vogue, GQ, Glamour, National Geographic—plus animal-themed wall calendars and patterned wallpapers.

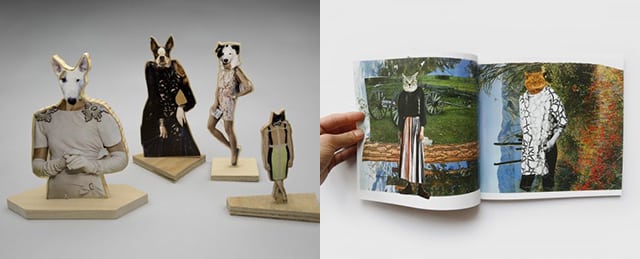

Working out of Creative Growth Art Center—a nonprofit that serves more than 160 artists with developmental, mental, and physical disabilities—John spends hours decapitating images of fashion models with scissors, then affixing their bodies to cut-outs of animal heads. Placed against scenic backdrops, these stylish chimeras fuse self-serious, airbrushed fashion photography with animal kingdom oddities: A guinea pig struts in a sequined tunic; a snowy owl carries a leather handbag through the woods; a ginger cat models a silk ball gown; a Yorkshire terrier strikes a pose in a frilly white pantsuit.

Since joining Creative Growth in 2003, John has become an unlikely art world darling. His animal-human mashups are routinely featured in contemporary art fairs like NADA Miami, the Independent, and Frieze New York. Talking Heads frontman David Byrne and artist Cindy Sherman are among the high-profile collectors of his work. In 2012, John’s work was the focus of a major group exhibition at Gallery Paule Anglim, San Francisco. In New York, he’s exhibited at White Columns Gallery and Rachel Uffner Gallery.

He got a late start: Until age 54, “I had no idea that I could do art,” John says.

Until age 54, “I had no idea that I could do art,” John says.

Born in Sturgis, Kentucky in 1949 and raised in Omaha, Nebraska by his cement contractor father and homemaker mother, John has struggled with severe learning disabilities since childhood. “My mom supported me a lot, but I never had any education,” he says. “I had problems with my eyes and with dyslexia. A bad case of that. Every time I tried to learn to read, I got a bad headache.”

When John was ten, his father died. After that, “everybody was telling my mom to send me away,” he says. “Back then, they thought it was a good idea to send disabled people away.” Eventually, his mother sent him to an institution in Brownsville, Texas. “They started giving me a lot of pills, drugging me a lot,” he says. “I really didn’t care for it. I remember being all druggy. I got to a point where I just didn’t take the pills. I’d hide them in my mouth and spit them out. They didn’t know that. They weren’t treating people right. So I finally called my mom and told her about it and she got me out of there.”

John moved to the Sara Center, a residential center for people with disabilities in Fremont, California, and stopped taking medications, except to manage his diabetes. Compared to the hellish institution in Brownsville, Sara Center was idyllic. There, he met his wife, Carol. “Basically, it was love at first sight,” he says. “We were married up on a hill.” At Sara Center, the couple lived independently, “getting along real well.”

But for decades, “I didn’t have any hobbies,” John says. “[I was doing] nothin’ much, just sitting in the house, watching TV, getting bored. I never really looked at art.”

That changed in 2003, when a friend referred John and Carol to Creative Growth. There, John discovered woodworking, rug-making, and ceramics. He and Carol also found a solid group of friends, who call him “Grandpa.”

“John’s kind of the patriarch in the community,” Creative Growth studio manager Matt Dostal says. “He brings in elaborate lunches for everybody in his friend group—a big cooler full of huge amounts of fried chicken and potato salad and diet Cokes.”

At first, John was critical of his visual art, and didn’t feel like he had a natural knack for it. But in 2007, visiting artist Paul Butler brought his traveling “Collage Party” to Creative Growth, inviting the artists to participate in a day-long cutting-and-pasting frenzy. “Collage can be really accessible for people who have a hard time drawing or painting,” Dostal says. “It’s a good gateway practice.”

At Paul Butler’s Collage Party, John made his first animal-human mashup. It was an instant hit. Fusing fashion and animal photography became his go-to practice. Though most of his works are variations on this same theme, they’re never formulaic; each collage introduces an exotic new hybrid species. His creatures often look somehow more natural than the chiseled, Photoshopped bodies that fill the pages of glossy magazines; it’s as if John is on a mission to tear off fashion models’ suffocating human masks and free the wild animals hiding beneath.

John is on a mission to tear off fashion models’ suffocating human masks and free the wild animals hiding beneath.

“His collages are in some ways incredibly simple, but there’s a really elegant subtlety, thoughtfulness and humor to the way he cuts out the images,” Dostal says. “They look so happenstance and poetic.”

“I just like switchin’ things around,” John says when asked why he gravitates toward collage. In recent years, John has expanded his practice to include 3-D art books and animated video pieces, such as “A Call to Kill,” in which an Australian Silky Terrier driving a sports car thwarts a villain’s plot to blow up the Golden Gate Bridge. Most recently, John had a solo show at Good Luck Gallery in Los Angeles’ Chinatown, where four pieces sold within the first two hours of the opening.

The success hasn’t gone to his head. “He doesn’t care what people think,” Dostal says. “He just wants to create his art.”

On June 14th, John and Carol celebrated their thirtieth wedding anniversary. “I’ve had a good life,” John says. He recalls how, in 2013, after being nominated by esteemed British curator Matthew Higgs, he won the Tiffany Grant—a biennial award given to American contemporary artists who demonstrate unique “talent and individual artistic strength” but haven’t yet received widespread recognition. Selected by a jury composed of artists, critics, and museum professionals, awardees receive an unrestricted check for $20,000.

John spent his prize money on a three-day trip to Disneyland with his wife and all their friends.

This is part two of four of Folks’ series of profiles of some of the amazing artists at Oakland’s Creative Growth Arts Center, which serves artists with developmental, mental and physical disabilities.

For original article, visit folks.pillpack.com.