The Beautiful Story Of An Artist With Down Syndrome Who Never Spoke A Word: Judith Scott’s twin sister Joyce tells her story. by Priscilla Frank September 6, 2016

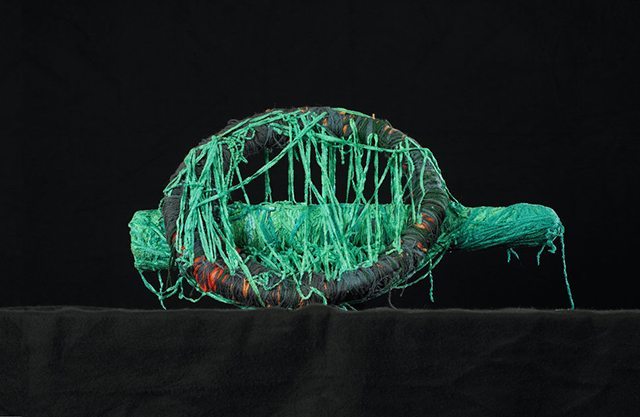

Judith Scott’s sculptures look like oversized cocoons or nests. They begin with regular objects ― a chair, a wire hanger, an umbrella, or even a shopping cart ― which are swallowed up whole by thread, yarn, cloth and twine, swathed as frenetically as a spider mummifies its prey.

The resulting pieces are tightly wound bundles of texture, color and shape ― abstract and yet so intensely corporeal in their presence and power. They suggest an alternate way of seeing the world, not based on knowing but on touching, taking, loving, nurturing and eating whole. Like a wildly wrapped package, the sculptures seem to possess some secret or meaning that can’t be accessed, save for an energy that radiates outward; the mysterious comfort of knowing that something is truly unknowable.

Judith and Joyce Scott were born on May 1, 1943, in Columbus, Ohio. They were fraternal twins. Judith, however, carried the extra chromosome of Down Syndrome and couldn’t communicate verbally. Only later, when Judith was in her 30s, was she properly diagnosed as deaf. “There are no words, but we need none,” Joyce wrote in her memoir Entwined, which tells the confounding story of her and Judith’s life together. “What we love is the comfort of sitting with our bodies near enough to touch.”

As a kid, Joyce and Judith were wrapped up in their own secret world, full of backyard adventures and made-up rituals whose rules were never said out loud. In an interview with The Huffington Post, Joyce explained that during her youth, she wasn’t aware that Judith had a mental disability, or even that she was, in some way, different.

“She was just Judy to me,” Joyce said. “I didn’t think of her as different at all. As we got older, I started realizing that people in the neighborhood treated her differently. That was my first thought, that people treated her badly.”

When she was 7 years old, Joyce awoke one morning to find Judy gone. Her parents had sent Judy to a state institution, convinced she had no prospects for ever living a conventional, independent life. Undiagnosed as deaf, Judy was assumed to be far more developmentally disabled than she was ― “uneducable.” So she was removed from her home in the middle of the night, rarely to be seen or spoken of by her family again. “It was a different time,” Joyce said with a sigh.

When Joyce went with her parents to visit her sister, she was horrified at the conditions she encountered at the state institution. “I’d find rooms full of children,” she wrote, “children with no shoes, sometimes with no clothes. Some of them are on chairs and benches, but mostly they are lying on mats on the floor, some with their eyes rolling, their bodies twisted and twitching.”

In Entwined, Joyce chronicles in vivid detail her memories entering adolescence without Judith. “I worry that Judy might be forgotten completely if I don’t remember her,” she writes. “Loving Judy and missing Judy feel almost like the same thing.” Through her writing, Joyce ensures that her sister’s painful and remarkable story will not be forgotten, ever.

Joyce recounts the details of her early life with startling accuracy, the kind that makes you question your ability to render your own life story with any sort of coherence or verisimilitude. “I just have a really good memory,” she explained over the phone. “Because Judy and I lived in such an intense physical, sensate world, things were kind of burned into my being much more strongly than if I spent a lot of time with other kids.”

As young adults, the Scott sisters continued living their separate lives. Their father passed away. Joyce got pregnant while in college and gave the child up for adoption. Eventually, while speaking on the phone with Judy’s social worker, Joyce learned that her sister was deaf.

“Judy living in a world without sound,” Joyce wrote. “And now I understand: our connection, how important it was, how together we felt each piece of our world, how she tasted her world and seemed to breathe in its colors and shapes, how we carefully observed and delicately touched everything as we felt our way through each day.”

Not long after that realization, Joyce and Judy were reunited, permanently, when Joyce became Judy’s legal guardian in 1986. Now married and a mother of two, Joyce brought Judith into her Berkeley, California, home. Although Judith had never displayed much interest in art before, Joyce decided to enroll her in a program called Creative Growth in Oakland, a space for adult artists with developmental disabilities.

From the minute Joyce entered the space, she could sense its singular energy, founded upon the urge to create without expectation, hesitation or ego. “Everything radiates its own beauty and an aliveness that seeks no approval, only celebrates itself,” she wrote. Judith tried out various media introduced to her by the staff ― drawing, painting, clay and wood sculpture ― but expressed interest in none.

One day in 1987, however, fiber artist Sylvia Seventy taught a lecture at Creative Growth, and Judith began to weave. She started by scavenging random, everyday objects, anything she could get her hands on. “She once grabbed someone’s wedding ring, and my ex-husband’s paycheck, things like that,” Joyce said. The studio would let her use nearly anything she could grab ― the wedding ring, however, went back to its owner. And then Judith would weave layer upon layer of strings and threads and paper towels if nothing else was available, all around the core object, allowing various patterns to emerge and dissipate.

“The first piece of Judy’s work I see is a twinlike form tied with tender care,” Joyce writes. “I immediately understand that she knows us as twins, together, two bodies joined as one. And I weep.” From then on, Judith’s appetite for art-making was insatiable. She worked for eight hours a day, engulfing broomsticks, beads, and broken furniture in webs of colored string. In lieu of words, Judith expressed herself through her radiant hulks of stuff and string, bizarre musical instruments whose sound couldn’t be heard. Along with her visual language, Judith spoke through dramatic gestures, colorful scarves, and pantomimed kisses, which she would generously bestow on her completed sculptures as if they were her children.

Before long, Judith became recognized at Creative Growth and far beyond for her visionary talent and addictive personality. Her work has since been shown in museums and galleries around the world, including the Brooklyn Museum, Museum of Modern Art, the American Folk Art Museum and the American Visionary Art Museum.

In 2005, Judith passed away at 61 years old, quite suddenly. On a weekend trip with Joyce, while lying in bed alongside her sister, she simply stopped breathing. She had lived 49 years beyond her life expectancy, and spent nearly all of the final 18 making art, surrounded by loved ones, supporters and adoring fans. Before her final trip, Judith had just finished what would be her last sculpture, which, strangely, was all black. “It was so unusual she would create a piece with no color,” Joyce said. “Most of us who knew her thought it as a letting go of her life. I think she related to colors in the way all of us do. But who knows? We could not ask.”

This question is interwoven throughout Joyce’s book, repeated again and again in distinct yet familiar forms. Who was Judith Scott? Without words, can we ever know? How can a person who faced unknowable pain alone and in silence, respond only, unimaginably, with generosity, creativity and love? “Judy is a secret and who I am is a secret, even to myself,” Joyce writes.

Scott’s sculptures, themselves, are secrets, impenetrable heaps whose dazzling exteriors distract you from the reality that there’s something underneath. We will never know the thoughts that ran through Judith’s mind while she spent 23 years alone in state institutions, or the feelings that pulsed through her heart as she picked up a spool of yarn for the first time. But we can see her gestures, her facial expressions, the way her arms would fly through the air to properly nestle a chair in its fair share of tattered cloth. And perhaps that’s enough.

“Having Judy as a twin has been the most incredible gift of my life,” Joyce said. “The only time I felt a kind of absolute happiness and a sense of peace was in her presence.”

Joyce currently works as an advocate for people with disabilities, and is engaged in establishing a studio and workshop for artists with disabilities in the mountains of Bali, in Judith’s honor. “My strongest hope would be that there are places like Creative Growth everywhere and people who have been marginalized and excluded would be given the opportunity to find their voice,” she said.