A Little Birdie Told Me

Work by Rosena Finister Essay by Danielle Wright August 2016

To spread joy, you must have it first; or so I’ve heard. Ms. Rosena Finister, a veteran artist at Creative Growth Art Center in Oakland, California, embodies this in an elegantly understated manner. Her joy is as unassuming as it is genuine. I first meet her during a visit to Creative Growth on a blustery Wednesday last fall. It’s lightly raining outside, but inside I am treated to a warm welcome from both the on-site studio manager that day, Matt Dostal, and the marketing and community development manager, Jessica Daniel. Matt tours me around with unswerving patience, fielding all types of requests, exclamations, assertions, and anecdotes with impressive grace and humor.

Creative Growth is an art studio for adults with developmental disabilities founded over 40 years ago by wife and husband team Florence and Elias Katz. Elias was a staff psychologist at the Sonoma State Hospital and Florence was an artist and instructor for both high school and college students. As legend has it, the Katzes hatched the idea for their signature studio model after hosting a private art-making event for a number of artists with disabilities. They were then granted a National Endowment for the Arts award, which they leveraged to establish Creative Growth in Oakland in 1972 — the premier institution dedicated to fostering artists with disabilities. With regard to national and international attention in the contemporary art world, Creative Growth is the most widely recognized of the trio of studios the Katzes have established in the Bay Area (with NIAD and Creativity Explored rounding out the suite).

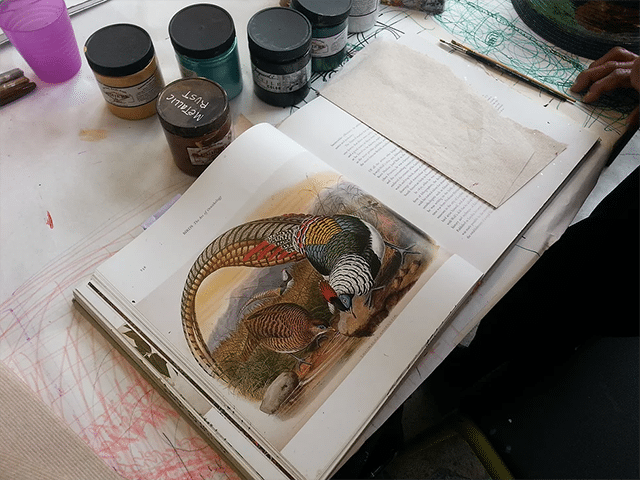

When we pass her workstation, Ms. Finister is quietly, carefully hand-embellishing what looks like a denim Kangol hat. I remark on the luminescent bird she is conjuring up and Matt informs me that the piece is part of a head-to-toe ensemble that Ms. Finister is painstakingly painting by hand for Creative Growth’s annual fashion show, part of their signature fundraiser. I am told by Matt that some artists work year-round on pieces to be auctioned at the event. I never see the whole garment, but I’m taken by Ms. Finister’s delicate touch and her off-hand remark about how the birds speak to her. I wonder about what they might be saying and make a note to come back to inquire about that after the tour concludes. There is a bird-like quality to her as well. She is extremely petite, less than five feet tall, and crowned with a puff of downy, jet-black hair that boosts her height another inch or two.

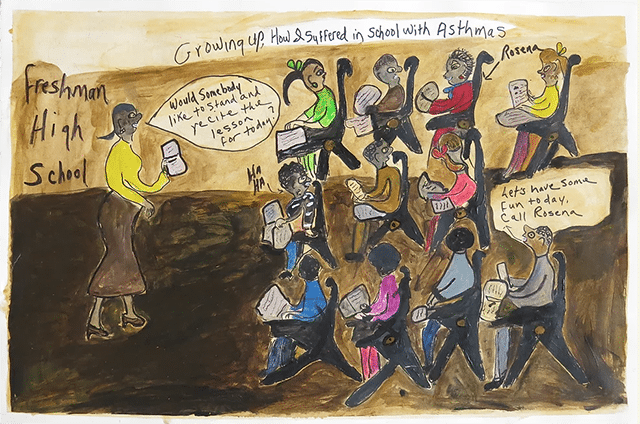

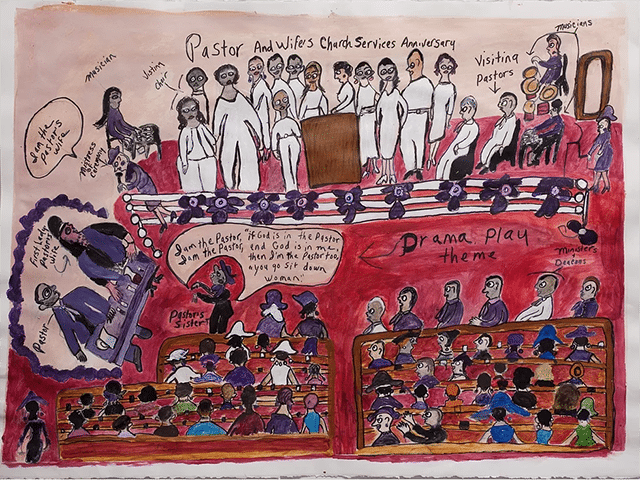

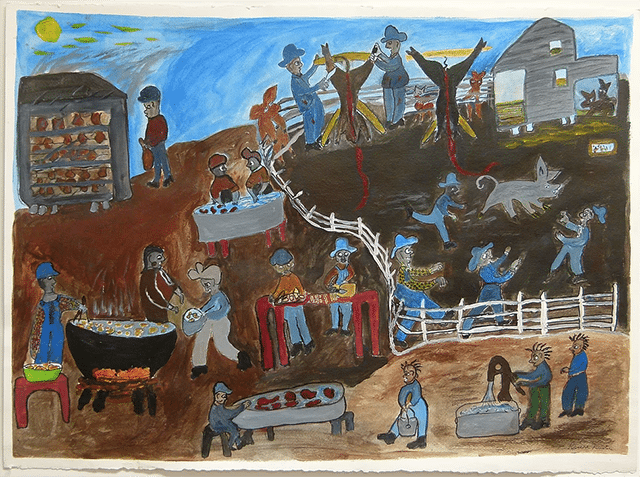

I am brought through different sections of the studio — woodworking in one area, textiles in another. The space is awash in silvery light from the big picture windows and abuzz with activity, with people milling and flitting about. There is even a quiet workspace upstairs that functions a bit like a private studio for artists who thrive with reduced noise and activity. I see their newly revamped animation studio area, including a section of wall painted Day-Glo green for video compositing. The tour ends where it began, in the eclectically decorated gallery near the entryway. I am momentarily distracted by the variety of work on display in the exhibition (Holiday 2016: Revel) and notice a piece or two of Ms. Finister’s; one depicts a bucolic scene of figures picking sweet potatoes, and another portrays a lively party full of slim, nimble-looking figures playing music and waltzing to inaudible tunes. I remember that I want to chat with her about her birds and quickly make my way back to her station. Ms. Finister is a pleasure to converse with, but I have to strain to hear her over the low hum of activity in the studio. When I do, I detect the faint hint of an accent, a bit of Southern charm. She has a delightful way of punctuating sentences with a hushed, “You know?,” a refrain that gives her speech a unique and gentle cadence. I ask her where she’s originally from and with her soft voice, she begins her story.

Ms. Rosena Finister grew up in Louisiana picking cotton on her family’s farm. It was hard physical labor. She describes how her family dug potatoes: The kids and relatives would trot behind the mule-driven plow and collect the spuds, depositing them on a wagon trailing behind. They also grew corn and peas and raised livestock. They raised pork and had a cow, which she learned how to milk. She briefly mentions that she is one of five sisters and, I believe, at least as many brothers. I do not catch exactly how many siblings she has, but I know the number isn’t a small one.

When she was a little girl, her family members would sit around and tell stories and she would write them down. They did not have a typewriter so she had to hand-write her tales. This, she says, is how she learned to pay attention to the details. She tells me she moved to the Bay Area over 50 years ago and shocks me when she alleges to be a ripe 72 years of age. “I’m an old lady,” she says with laughter in her voice.

As a single mother of three, she worked all manner of odd jobs to keep food on the table. From sewing garments to soldering, Ms. Finister was truly a Jane-of-all-trades. She chuckles when she tells me that she burned many a hole through her clothing with the soldering iron while testing transformers. She explains that she had divorced early and that the father of her children refused to pay child support. She says it was rough, that she had to work all of her life. Two of her children live nearby in Oakland. One of her two sons moved to Stockton to raise a big family. Her other son resides in Oakland and is between jobs and does not have children. Her daughter also lives in Oakland and has kids. Ms. Finister has six grandchildren all together, some of whom she occasionally babysits.

There is a considerable gap, fifteen years or so, between her only girl and her youngest boy. I am curious about this but I don’t pursue it. She mentions that her ex-husband liked to garden but when they split she let the yard grow over. She was done with it, she reports. Like other activities that she has let fall by the wayside, it was just too much work to maintain. “When I got rid of this husband, I wanted to rest.” I can understand this considering the farm-to-table nature of her upbringing. Growing up, her parents were very strict and discipline was a significant part of her life from an early age. It was different for her children. “Kids got to do what they want to do,” she muses, “pick up what they want to pick up.

While she didn’t have time to make visual art when her kids were young, she enjoyed writing short poems and rhymes for them. “Like kid stuff,” she describes. I ask her to share one with me and she recites:

“Red, White, and Blue the monkey favors you.”

I wait for elaboration, but that’s all there is to it. We laugh. She intimates that it’s not exactly a masterpiece — not quite like something written by Maya Angelou. I recollect that Maya Angelou was a woman of many talents as well, notably a dancer early on in her career. This seems to surprise her. I say that the two of them aren’t all that different, which she summarily brushes off.

Up to this point, it doesn’t seem like much of anything rustles Ms. Finister’s feathers. I am surprised when she describes how she is downright scandalized by the price of short ribs these days. She recalls wistfully how steaks used to be thicker, bigger, and cost less. She recounts how she used to stretch $25 to buy groceries for her and her kids for a week and regales me with prices from times past — a gallon of milk and a half gallon of ice cream for 50 cents a piece. It’s hard for me to fathom.

Ms. Finister continues to be a busy individual despite her children having grown up, splitting her time between church, children, grandbabies, and making art. I’m amazed when she says she hadn’t learned to draw before she came to Creative Growth. Here she’s tried her hand at a range of media, including textiles, drawing, painting, and animation. When she isn’t painting or drawing, she is taking dance and computer animation classes. She informs me she doesn’t do hand-sewing or quilting anymore because it is simply too much work, and besides, she wonders aloud, who wants to buy a handmade quilt? When I mention that someone like me might be interested, she lets the comment slip by without a remark. She’s sharp, but her perceptiveness is tempered by an easy-going attitude. She can’t be bothered to waste energy fussing over things she deems inconsequential. I can’t picture her becoming overwrought about anything, really. She is direct and present-tense in a refreshing way. Her demeanor has a way of putting others at ease.

Ms. Finister’s presence at Creative Growth is a bit of an anomaly. She was somehow grandmothered into the studio without having to go through the usual channel — a social worker referral through Golden Gate Regional Center. By some divine fortune, she found her way to Creative Growth and both the former studio manager and executive director had the good sense to let her in.

She’s known the current studio managers, Julie Alvarado and Matt Dostal, for about two years and speaks highly of them both. When I ask who inspires her, she gives me both names and indicates that it was Julie who taught her how to paint. A veteran artist of Creative Growth who has worked at the studio for over 20 years, Ms. Finister tells me that she loves to make art. She says working at Creative Growth studio is like a dream.

In her piece, “Ordinary People Swinging with the Movie Stars,” she dances alongside Whitney Houston and Mary J. Blige, while Matt, the Creative Growth studio manager, strums the guitar, and one of Creative Growth’s administrative staff taps out a rhythm on the drums. It seems appropriate that the studio manager would create the melody while the administrator keeps a steady beat. When I ask her about dancing, she declares that she loves to boogie. She explains that she just likes to move and doesn't have time to learn a particular dance.

As for her hand-painted garment, she says the birds in the reference image convey messages to her. In her dazzling imagination, when she sees a picture she sees a story. The relationship between the elements of the image seems to develop gradually in her mind. She says she likes a bit of quiet so she can ponder and process her tales. She says she sometimes only needs a few hushed moments to get her bearings. This resonates with me. As she seems to keep herself rather busy, she admittedly doesn’t have much time to weave tall tales. It begs a question that I can’t resist: if she had all the time in the world, what would she do? She answers, “I don’t know, I just do what I do. Painting and drawing, go and learn other stuff about art.”

Ms. Finister continues to whittle down her activities, cutting out things like the church newsletter she used to produce because, according to her signature refrain, “it was too much work.” She spent too much of her money and time buying paper and producing content to justify her involvement. She has worked hard physical labor all of her life (including raising three kids without support) and I wholeheartedly believe her when she says a given activity is no longer worth the effort.

When I ask about her piece depicting the potato harvest, she tells me about the barn (or “the crib,” as her family called it) where they once stored potatoes. They would cover them with hay to preserve them after harvest and bury the flowers during planting season to begin the cycle anew. She tells me that most of the food they ate, they grew. I marvel over the idea of having that kind of visceral relationship to food. It seems as if she’s been making things with her hands for her whole life.

When she is not painting scenes of the farm (of which she has sold many), she depicts all manner of other subjects. You see, Rosena Finister finds stories everywhere, whether it’s about the man who hustled her for 5 cents when she was downtown shopping or the man she encountered one day wearing a dress and insisting folks clear the reserved seating at the front of the bus for elderly folks and those with disabilities. She writes them down on paper and, in her own words, she’s made “a couple of books,” but has only printed one once.

When asked if she considers herself an artist, she responds, “Yeah I do, I’m making money.” She says even if she wasn’t making money from her art, she’d still enjoy the process. When I ask her what she cares about, she says, “I care about a lot of things. I really care about me.” She pauses there and I can’t suppress a burst of appreciative laughter, reveling in the beauty of her self-assuredness. She goes on, sharing how she cares about family, about people, her children (pronounced “chilren,” which tugs at my heart-strings; her phrasing evokes fond memories of my grandfather who was born in Georgia), her grandchildren… She professes her love of people, and how she’s willing to do anything for them. It’s important to Ms. Finister to care for people, to communicate, and to “blend in well.” I’m curious what she means by “blending in,” but I have more questions and I’m running out of time.

With regard to being an artist, she likes that she can make work on her own schedule and that it affords her the freedom of choice. I ask her what she likes the least about being an artist. She says she can’t think of anything. I think this is a wonderful answer, even if I can’t relate. Ms. Finsiter’s creativity extends to her clothing. She makes her own neckties. She says she’s always cutting up fabric and making new clothing. It seems to me that the way she dresses is part of her work. The combination of vibrant reds and phthalo blues offset by a cool bluish green is eye-catching without being ostentatious.

Our conversation meanders on. I ask her what she’s most afraid of. She doesn’t have a response to this so I suggest that perhaps she is fearless. She shies away from that assertion. She’s not being falsely modest, just factual. She suggests that perhaps “fearless” isn’t the most appropriate term. She seems to have a healthy awareness of her age, but she doesn't allow it to put undue limitations on the variety of her daily activities. Though she’s careful not to overwork herself, when there’s something she wants to do she just goes on and does it. I can’t think of a better way to sum up my impression of her. She doesn’t put on a show of humility and she isn’t braggadocious. She just is who she is and she does what she likes. It’s as simple and as profound as that.