Charting Experience: Four Artists with Developmental Disabilities Map Singular Visions By Sola Agustsson August 6, 2016

The process of creating art always involves transmitting one’s singular sensory experiences into a discrete vision. The Los Angeles exhibition Mapping Fictions brings together four contemporary artists who organize information and experience through text and images, charting popular culture, physical space, and personal knowledge in painstakingly detailed work. Andreana Donahue and Tim Ortiz of Disparate Minds curated the exhibition, which is now on view at The Good Luck Gallery, a space dedicated to self-taught artists. Disparate Minds is an organization that follows progressive art studios, described as “studio environments where adults with developmental disabilities can pursue and maintain lives/careers as artists.” Each of the artists in Mapping Fictions is neurologically or developmentally atypical, and works at a different progressive art studio.

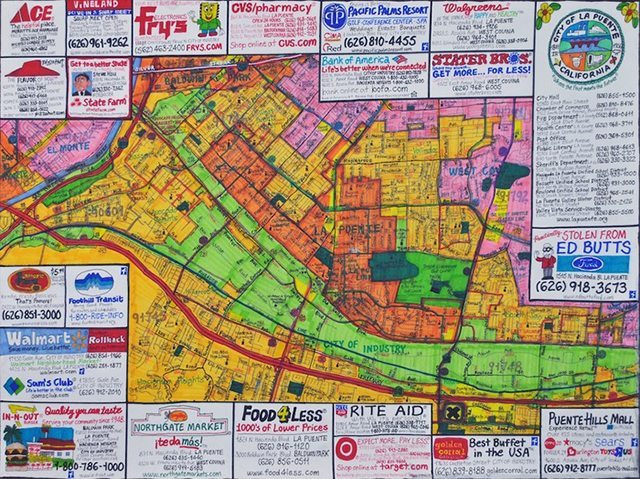

Joe Zaldivar’s work reimagines screenshots from Southern California found on Google Street View. The snapshots are ephemeral, but his drawings of maps, buildings, and interiors reference specific local businesses. The titles and representations of these places are straightforward, pinpointing the moment in time quite factually. Yet, the drawings are subtly, humorously laced with cultural references. Bart and Homer Simpson, for example, turn up in The Coffee Roaster, 13567 Ventura Boulevard, Sherman Oaks, California, among other works.

Zaldivar’s YouTube channel has drawn over 2,000 followers, and lends insight into his particular vision. Recording directly from broadcast television, as well as VHS tapes he’s found at yard sales, Zaldivar pieces together seemingly isolated scenes. News segments, commercials, and movie clips from past and present blend together as white noise. But because he records them by hand, cam-style, the videos are a little shaky. It’s an idiosyncratic archive; inserting his presence into the documentation, Zaldivar hones in on recorded moments that are soon to be forgotten. His works highlight the markers of time, location, and pop culture as essential tools for processing information and charting our lives.

Daniel Green similarly turns his gaze on daytime television. His Days of Our Lives series structures personal events with the scheduling of popular soap operas. He intersperses the hourly schedules with illustrations of characters, logos, and personal commentary onto his mixed media on wood pieces, graphing them like TV Guides. The Sun (2010) reveals much about Green’s mapping of information by merging each December of the artist’s life with a television program from that time, reflecting on a universalized nostalgia for the cable television of our childhood. Now that we live in an era where television is as often streamed as it is broadcast at a set time, watching TV can be a less communally timed experience. But in the 1980s and 1990s, you had to be glued to a television to watch a show—and you could be sure thousands of other people were watching too.

Like Zaldivar, Green also combines pop culture iconography with the personal. In his portrait of the cast of Star Trek, for example, the artist infused facial features from his friends onto the television characters.

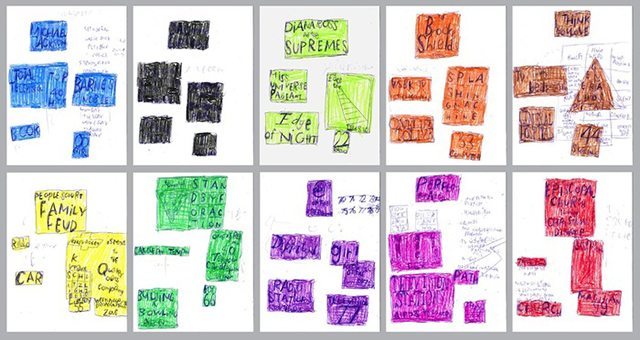

On the surface, many of these works and their organizational principles seem chaotic, yet there is a distinct order in the way each of the artists construct their works. Roger Swike draws his textual graphs intuitively at first, adding more deliberate details as he moves through the process. Later, he places them into color-categorized folders. Creating a lexicon of his own through numbers and pop culture references, he forms particular patterns in the pieces, which he later revisits to add further nuances to his own methods.

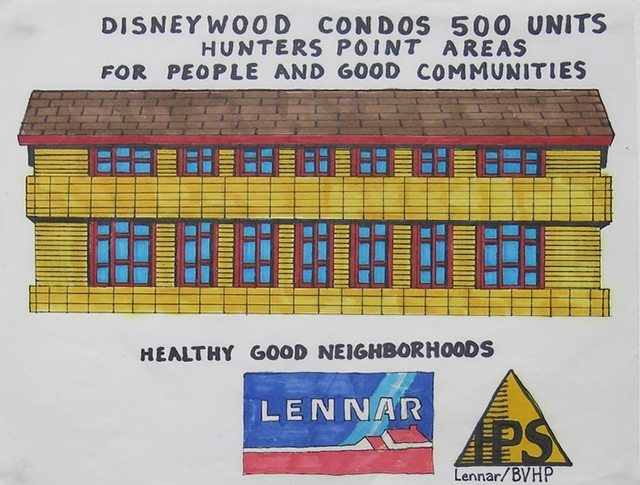

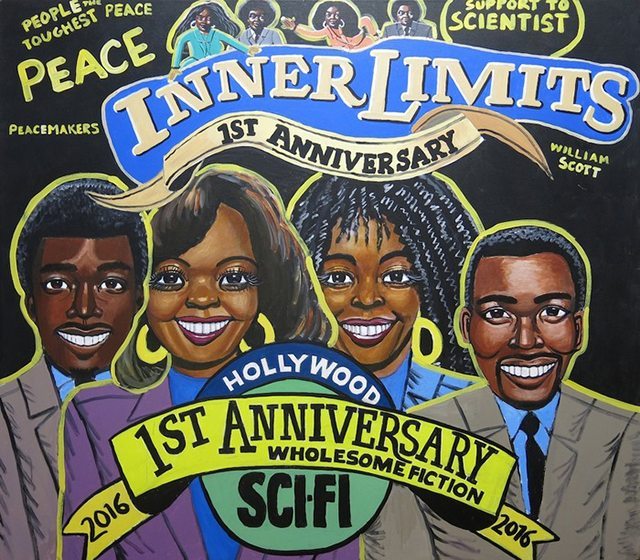

San-Francisco artist William Scott is interested in community-based organizing through activism and utopian philosophy. The exhibition includes some of the plans for Praise Frisco, the artist’s envisioning of a new city rising in the wake of a “cancelled” San Francisco, including a revitalization plan for his own socially marginalized area of Hunter’s Point. Ambitious and precise architectural drawings relay his idealist vision for the future.

All of the artists unlock ways of seeing the world through their work, specifically by incorporating text in their drawings and diagrams. Though we may not understand exactly how they view the world, through lists, architectural plans, maps, and pop culture symbols, we can concretely relate. List-making unifies in its inherent ability to convey how each person plans, schedules, and quantifies their existence—be it in the form of a daily routine or a list of goals. Pop cultural references bring together collective touchstones and experiences with the individual’s. And through maps and blueprints, a specific time and place can be mathematically pinned down. These methods of organizing and categorizing—list making, diagramming—give order and sense to all our lives. But the artists in Mapping Fictions show how these tools are not just personal, but communicative. They mediate their experiences of the past and dreams for the future in this public, yet intimate archive.

Sola Agustsson is a writer based in Los Angeles. She studied at UC Berkeley and has contributed to Bullett, Flaunt, The Huffington Post, Alternet, Artlog, Konch, and Whitewall Magazine.