Inside Creative Growth, the Always Inspiring Oakland-Based Incubator For Artists With Disabilities

By Fiorella Valdesolo

October 9, 2020

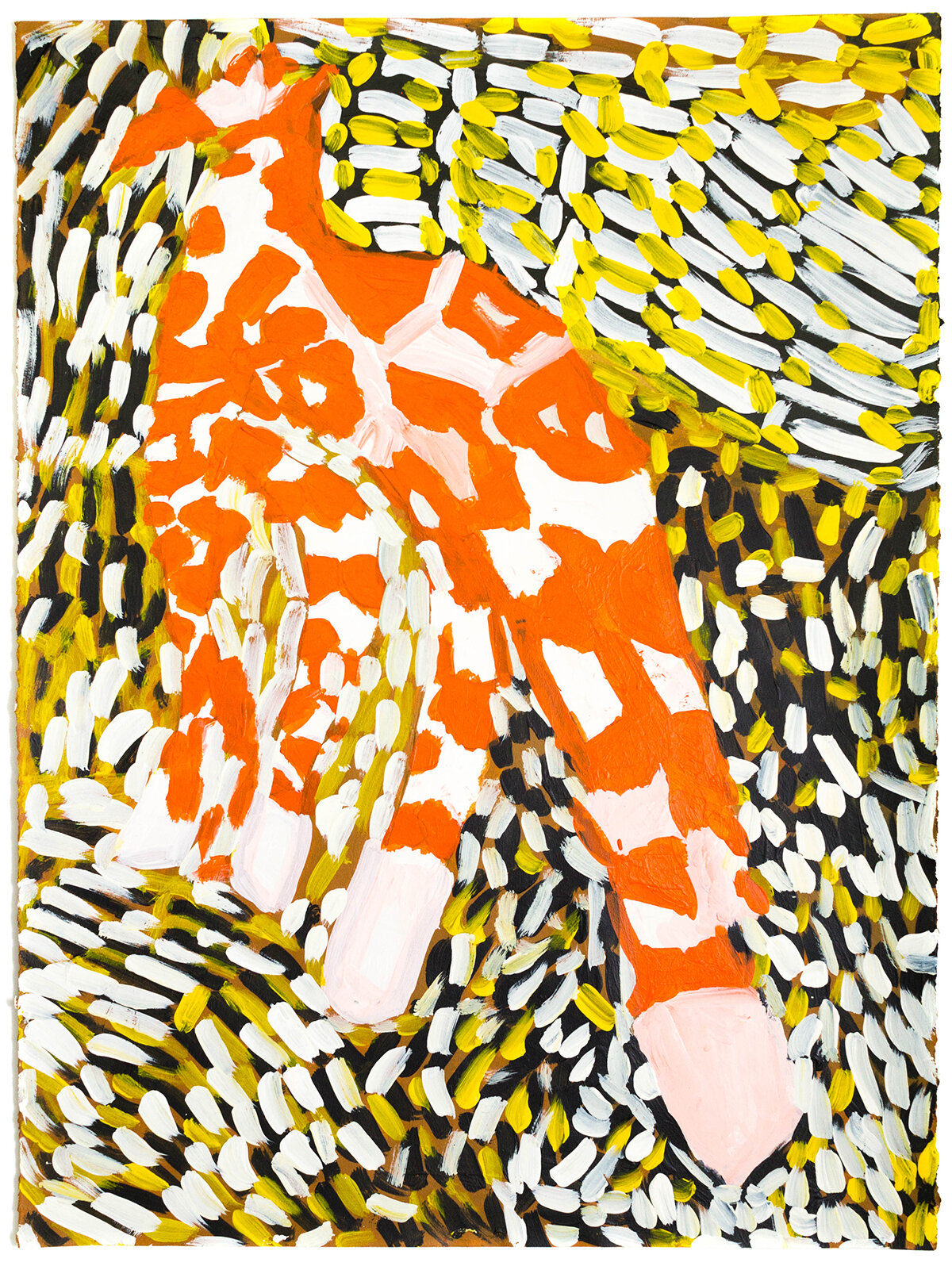

Work on paper by Ron Veasey

The purpose of Creative Growth, an art center for developmentally disabled adults founded in 1974 from the Berkeley garage of artist and art educator Florence Ludins-Katz and her husband, psychologist Dr. Elias Katz, is in its name: No matter who we are, engaging in a creative practice allows us to evolve. The Katzes were ahead of their time. This year marks the 30th anniversary of the signing of the Americans with Disabilities Act, a landmark proclamation designed to shield the disabled community from discrimination. By the time the law was passed in 1990, Creative Growth had already spent nearly two decades focused on forging a path for the disabled.

The center was born of the Katzes outrage about the number of patients being deinstitutionalized after California’s then-governor Ronald Reagan signed the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act, and, with no resources, ending up homeless or imprisoned. “They believed that art and creativity could be a way to break down barriers around disability and offer a new path forward for people,” says Tom di maria, Creative Growth’s director of external relations, and, before that, its director for 20 years. “Back then, people with disabilities were very hidden from the mainstream, so it was a radical idea.” In the years since its inception what would be more radical was the growth (and profitability) of Creative Growth’s artists in the mainstream art market. “When I was hired twenty years ago the Creative Growth board said, ‘We think the artists can be part of contemporary art culture in a way that they haven’t been yet, and that we can lead in this idea,’” says di Maria. “I’ve been trying to expand that concept since.”

Creative Growth has come a long way since its humble Berkeley beginnings: The sprawling center, which is still run entirely by artists — “I like to say we’re a learning environment, not a teaching environment,” di Maria adds — now boasts a roster of 160 artists with 100 scheduled every day. The majority come to the center (often from boarding care homes or referred by disability organizations) with zero art background and are given time and space to explore various mediums. Though they’re often billed as outsider artists, di Maria prefers the term “self-taught.” “Some of the ideas of what an outsider artist is resonate, that it’s someone who is not academically trained and what they make isn’t really influenced by the world around them but more of a pure spontaneous vision. But we don’t use that word for our artists because people with disabilities are often outside of culture and society so much that they don’t need another label,” he explains. Once artists begin at Creative Growth they can work there, for free, their entire life and many have been there for decades. “They can stay whether they make anything or not, so there is no need to produce, though something fantastic almost always happens,” says di Maria. “We give them the time it takes.”

The focus is not on the product, but the process. For Monica Valentine, who has been blind since early childhood and has prosthetic eyes, it’s about feeling colors by way of their temperature (a form of synesthesia) and then quickly and methodically threading brightly-hued beads to form dynamic tactile sculptures. While for Ron Veasey, his fastidious research (countless hours spent silently poring over books and magazines before beginning to sketch an idea out in pencil) is as long and intentional as his painting. “Our artists are 90% based on process,” says di Maria. “They make things, then they want to make the next thing, without any of the interest in the commercial aspect of what happens to their work… they just want to keep making.” That makers instinct is perhaps why many of the earliest champions of Creative Growth came not from galleries and museums, but from the design world. “Those involved in a creative practice themselves like designers, architects, and fashion insiders, they all have a great vision and don’t have to be told what they should like,” explains di Maria. “They always saw the work as exciting.”

While the work of Creative Growth artists has hung in the MoMA and Brooklyn Museum, has been emblazoned on designer accessories by Marc Jacobs, has been commissioned by Facebook, and has been scooped up by everyone from celebrities to the most prestigious galleries and dealers, there are still many people who are happening upon it for the first time. And social media has helped significantly in fanning the flames of discovery. “We’ve really seen a new audience grow since the pandemic and our visitorship has skyrocketed,” shares di Maria. “We found a new kind of connectivity that we didn’t have before.” Though how we view and consume art continues to morph, the mission of Creative Growth remains the same: to hand people the power to be creative. And, says di Maria: “For a person with a disability who’s often been directed their whole life about what to do and what not to do, it’s a very empowering lesson in growth.”

Here, 10 artists on the current Creative Growth roster whose work we find especially compelling.

Bruce Howell

Part of Creative Growth’s first wave of artists (he’s been at the center on and off since 1975) Howell’s work spans mediums but he is most prolific on paper, using watercolor, ink and acrylic and employing repeated motifs to create syncopated compositions in a saturated color palette that buzz with energy.

Carlos Fernandez

Fernandez renders otherwise unremarkable objects (a button, a clover) remarkable, using a reductive approach to highlight all the little nuances of their shapes and forms. Minimalist in nature, his geometric language is built on a foundation of bold linework and distinctive color choices.

Carrie Oyama

Unlike many of her Creative Growth peers, Oyama has an academic background in art as well: she graduated from the School of Visual Arts in the 1960s and was a part of New York’s Pedestrian Art Movement. Though when she arrived at the center in the 1980s her focus was on sculpture, Oyama has, in recent years, turned her attention to drawing and painting, using her non-dominant hand for wildly expressive depictions of the human body.

Cedric Johnson

Texas-born Johnson, who started practicing at Creative Growth in 1980, has, since then, developed into a multi-disciplinary master of abstractionism. His compositions on paper, an exuberant cacophony of line and pattern in an expansive color palette, can be appreciated at any angle (he constantly rotates the paper while working), while his ceramic masks, which imagine the human form through a similarly abstracted lens, have an absurd beauty.

Dan Hamilton

Born and raised in Argentina, and a member of Creative Growth since 1975, both Hamilton’s smoothly rendered ceramic animal-like forms and paintings are characterized by confident dense black linework and flat planes of color.

Donald Mitchell

Mitchell’s work has evolved dramatically in his time at Creative Growth (he’s been there since 1986) from crosshatched linework so heavy that it obscured any imagery beneath it to eerily beautiful paintings of unidentified figures in repetition that take on their own symbolism. Mitchell’s work is a darling of collectors and has been on display at Gavin Brown’s enterprise and the Milwaukee Art Museum, among others.

Marion Bolton

Bolton adeptly distills the essence of his subjects—most often animals or other elements from the natural world and various people inspired by his perusing of photographic images—by way of opaque color and quick, gestural strokes. It’s a particular gift that make his canvases feel very much alive.

Monica Valentine

Sometimes an artist’s process is visible in their work and Valentine, who has only been at Creative Growth since 2012, is a perfect example: The methodical rhythm with which she feels for her colors and then nimbly threads sequins and beads onto pins and then, finally, foam forms is discernible to the viewer. The extraordinary result: organic, almost fluid sculptures sprouting with color and texture.

Rickie Algarva

Algarva, now in her 70s and a part of Creative Growth since 1989, brings a psychedelic sensibility to her singular Surrealist work on paper and her rugs. Algarva’s fantastical visual language is informed by everything from Egyptian mythology to her favorite TV show, the History Channel’s Ancient Aliens, and the effect is otherworldly.

Ron Veasey

In his research of source material, his careful sketching, and then finally painting, Veasey, who has been with Creative Growth since 1981, is always slow and steady, intentional in his approach. His graphic portraits with their clever use of line and color are exceptional, and also unflinching in their connection between subject matter and viewer.

For the original feature, visit sightunseen.com.