CLAY CULTURE growing creatively

A community of artists working together at a non-profit in Oakland, California, is shattering stereotypes by finding ways to overcome disabilities while creating in-demand artwork that helps them to make a living.

By Dawn Starin

September 2017

One small, non-profit organization in Oakland, California, has been at the forefront of changing perceptions of what individuals with intellectual, emotional, physical, and/or developmental disabilities can do.

For over 40 years, the Creative Growth Art Center has focused on encouraging and supporting artists with disabilities by providing a professional studio environment for artistic development, gallery exhibition and representation, and nurturing a non-competitive, collaborative, and collective community of artists where both imaginative creativity and creative camaraderie blossom.

While the program is artist run and artist led, it does not, according to the director, Tom di Maria, “teach, guide, or steer people in one direction or another.” It does not offer therapy or instruction and it is not a drop-in center. There are no specific tasks, responsibilities, deadlines, or certain models of success and there are certainly no failures. In this non-competitive setting, the artists proceeding at their own pace in art-making are exercising total personal choice and personal control over their own work.

An Artistic Oasis

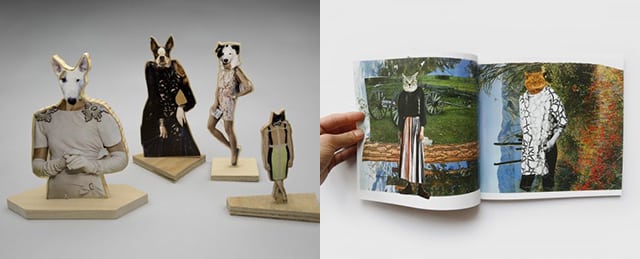

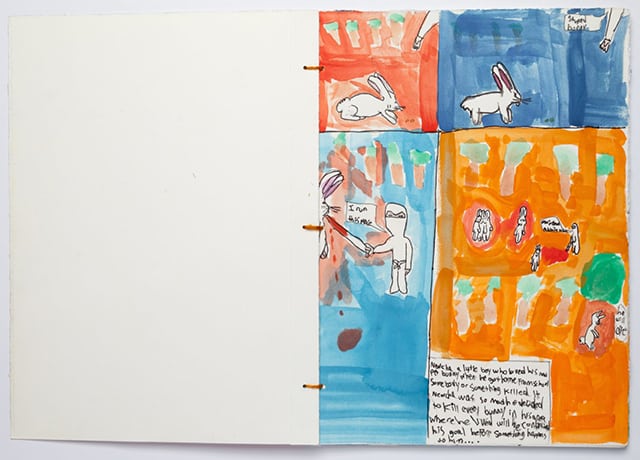

The center—thought to be the oldest exhibition space dedicated to the art of people with disabilities—is home to over 160 adult artists engaged in a range of artistic mediums: ceramics, collages, drawing, dressmaking, fiber arts, painting, photography, printmaking, rug making, tapestry, video animation, and woodworking. A variety of cultures, backgrounds, experiences, abilities, and disabilities are represented and many languages are spoken, though some artists do not speak or are unable to use language.

All of the artwork on display (and much of the work that is not on display) is for sale. Everyone here, even if they don’t sell anything, gets a quarterly check because there is a communal pool made up of proceeds from the sale of items priced at less than 25 dollars. This program not only provides the artists with an income, but also ensures that they receive recognition, encourages participation in a community while decreasing social isolation, and increases their sense of self-worth and self-sufficiency. Individuals who often have no access to complete self-expression and total creativity have been given an artistic oasis. And, the center’s safe and encouraging environment has made it possible for this community of creative individuals to reach out to the larger outside community and be accepted. Artwork fostered here has been the subject of articles, books, and films and has been included in numerous gallery shows, international collections, art fairs, and prominent museums throughout the world.

Possibly the most celebrated of the Creative Growth artists, the late Judith Scott, was born with Down syndrome and became deaf as an infant. In 2014 she had a one-woman show at the Brooklyn Museum’s Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art and today her sculptures sell for tens of thousands of dollars. Speaking about her sculptures, di Maria says “Her work is astonishing, rich, and varied. Her elaborate, enigmatic forms capture our imagination. I think of this work as a language understood only by the artist; a language without words for which there will never really be a translation. And, when we experience it, it resonates with us and we bring our own meanings to it.”

Walking around the center’s gallery and studio and witnessing the creativity and energy bouncing off the walls, floors, and ceilings and spilling out of the cupboards and off the shelves, it is clear that Scott is not the only master artist to have been nurtured here. It is also clear that the art created here has the ability to move an audience—perhaps the very definition of the value of art itself.

A Member Artist’s Perspective

Beanie-clad Cedric Johnson, a natural salesman, leads me through the studio and around the gallery, proudly showing me his work. Born in 1952, in Corpus Christi, Texas, Johnson has been creating a wide range of art forms at the Creative Growth Art Center in Oakland since 1980. Exuberant, extroverted, highly animated Johnson, who “always knew he wanted to be an artist,” works in a wide range of artistic formats—ceramics, sculpture, painting, drawing, textile work, and woodwork—there is very little he does not attempt. When he creates, which he does five days a week, ideas “come to him through his imagination, from what he sees around him in the studio, or from pictures,” according to Jessica Daniel, Creative Growth’s marketing and community development manager. Like Scott, and many of the other artists working here, his imagination is surprising and his work is both intense and astounding.

Johnson has exhibited in group shows at Creative Growth, as well as at Rena Bransten Gallery and Gallery Paule Anglim in San Francisco. Ampersand, a Portland, Oregon, gallery that specializes in contemporary artwork, held Cedric Johnson’s first solo exhibition where he exhibited 20 artworks, including 6 ceramic pieces.

Myles Haselhorst, the curator of the exhibition, met Johnson when visiting Creative Growth for the first time. Haselhorst recounts seeing Johnson drawing a mask-like face on the pages of an old atlas. “I’ve always been drawn to masks of all kinds,” Haselhorst notes, “so I was thrilled to see that nearly every page of the atlas featured drawings that were suggestive of masks one might see in primitive cultures, but in Johnson’s distinct visual style.” Like his drawings, many of his ceramic pieces allude to masks and hang directly on the wall. “It’s remarkable,” Haselhorst continues, “how Johnson is able to translate his drawing style to his ceramic pieces, each one portraying a different character or state of mind. They are a bit larger than life, which, in addition to his bold color choices, makes for pieces that have an otherworldly quality.”

While their various disabilities lend significance to the Creative Growth artists’ creations, they, and their work, are not simply defined or limited by these disabilities. Looking at Johnson’s vibrant, glossy, Cubist-style, fantastical ceramic masks and clay whistles, and the artwork from many of the other artists working here, it becomes clear that he and his community of fellow self-taught artists are shattering stereotypes, creating works of distinction, and achieving recognition in today’s art world.

Photographs by Justin Clifford Rhody

Photographs by Justin Clifford Rhody

7th Annual Beyond Trend Runway Event and Fundraiser

Saturday, April 8, 2017 at 6:30pm

2315 Webster Street in Oakland, behind Creative Growth Art Center

7th Annual Beyond Trend Runway Event and Fundraiser

Saturday, April 8, 2017 at 6:30pm

2315 Webster Street in Oakland, behind Creative Growth Art Center

Photographs by Justin Clifford Rhody

Photographs by Justin Clifford Rhody