Next stop: Oakland

Where Creative Growth, a center for artists with disabilities, is shepherding America’s next Andy Warhol

Story by Joshua David Stein Photography by Carlos Chavarría June/July 2017 Issue

L-I-G-H-T Space L-I-G-H-T Space L-I-G-H-T

The two-part click-clack of an old Brother word processor keyboard keeps time on the second floor of a converted auto body repair shop in Downtown Oakland, California. Since 1982, the large brick industrial space has housed Creative Growth Art Center, a gallery and busy workshop for artists with developmental disabilities. At the typewriter sits Dan Miller, one of the 160 artists who work with the organization.

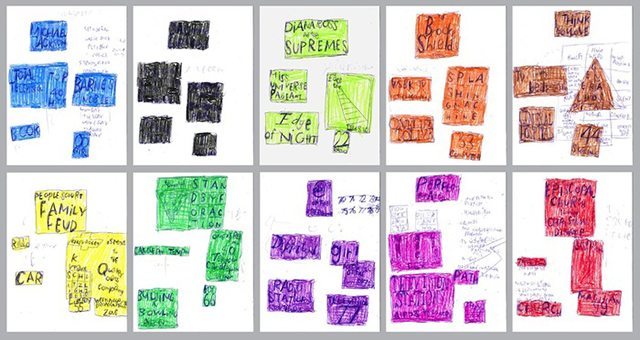

Like many of the artists here, Miller, 56, has autism. Today, he’s using a ream of paper that extends scroll-like out of his typewriter—“Dan Miller’s typewriter,” per the message Sharpied across the carriage—but he often draws or paints the words, over and over again, over and over one another, until their limbs form thick abstract clouds and their meaning becomes lost in a cartoon tussle of lines.

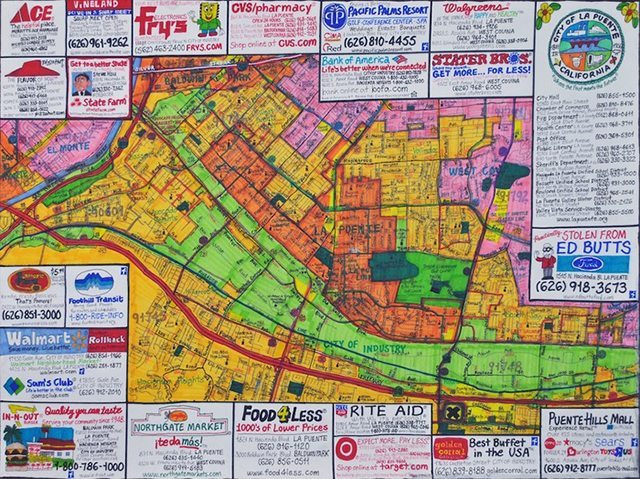

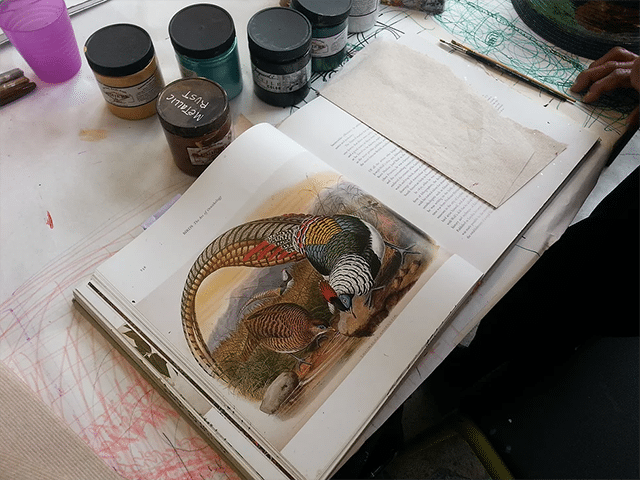

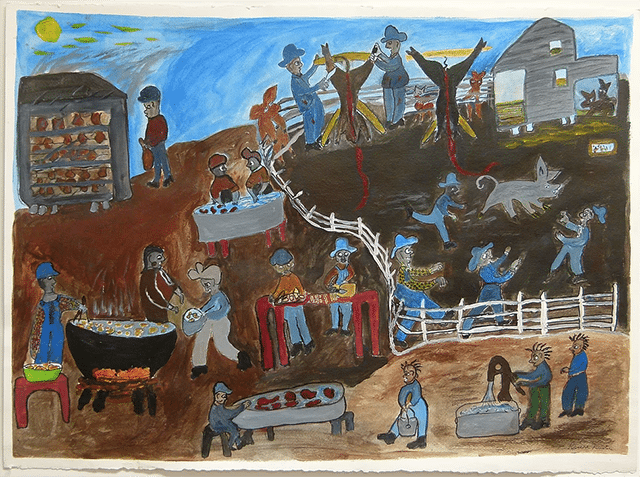

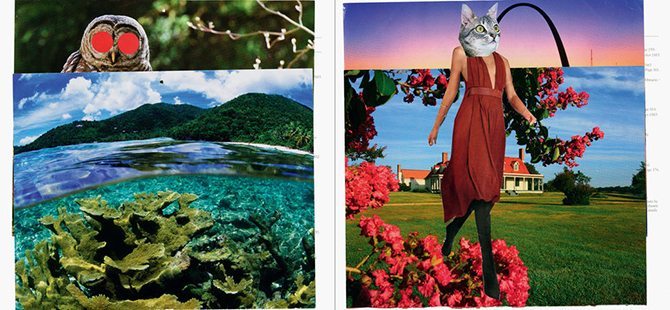

Miller is in one of the two smaller studios located on the second floor of Creative Growth. On the open floor below, tables covered in brown butcher paper—around which artists sit deeply and solitarily engaged in their work—are laden with a buffet of crayons, markers, pencils, and other art-making materials. At one table, Monica Valentine sits before a large Styrofoam cube and a tray of brightly colored beads, sewing pins and sequins. The funny and chatty 62-year-old has autism, and is wearing a green bicycle reflector as a necklace. She is also blind and claims she can sense the colors of her art materials by touch: blue is cold, yellow is warm, green is cool. She is in the process of covering the entire Styrofoam cube in a dense coat of beads and sequins, held together by pins, until the sculpture looks like a glorious geometric Technicolor porcupine. Meanwhile, Jane Kassner sits at another table, her walker beside her. A minimally verbal 62-year-old with Down’s Syndrome, she is working, as usual, on advertisements cut out of old Artforum magazines. She grabs a brush and paints over the slick ads for gallery shows in New York, London, and Tokyo. Beneath a swirl of brilliant orange paint disappears Andy Warhol’s Brillo box. With one stroke of blue paint, most of renowned artist Barbara Kruger’s words are obliterated. The only words showing are Look and listen.

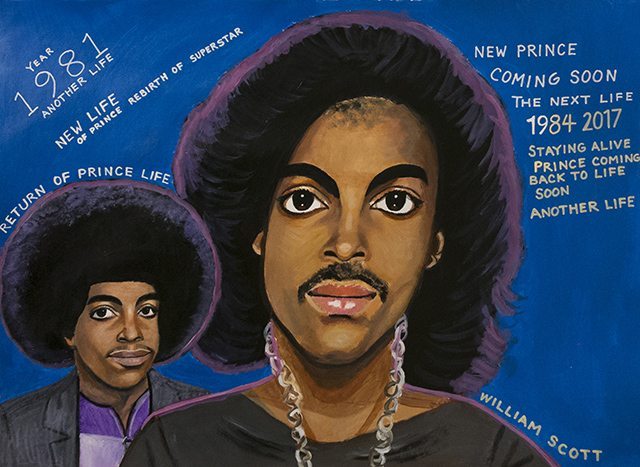

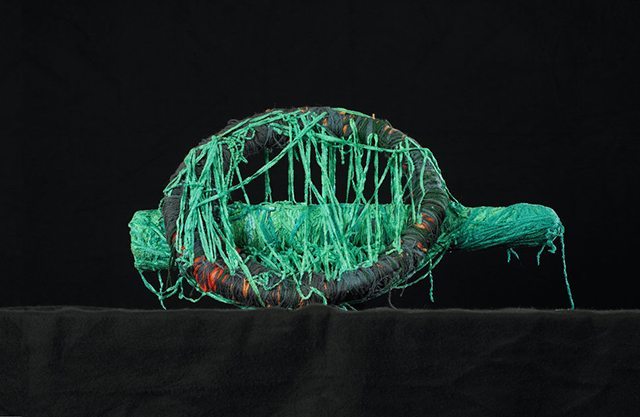

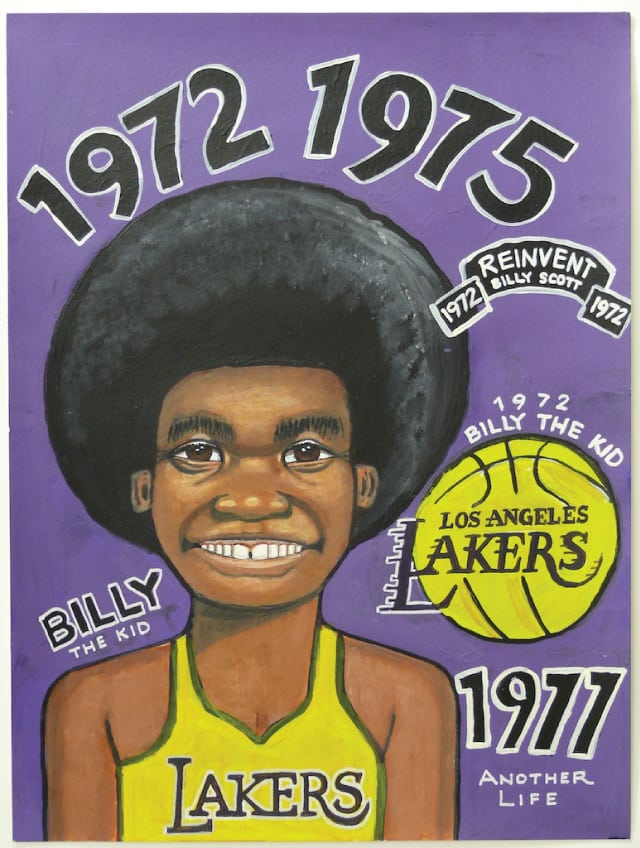

It’s tempting to read Kassner’s work as a biting critique of commodification in the art world, but the artist and her colleagues here at Creative Growth pay no heed to auctions, collectors, patrons, and galleries. Their indifference, however, is unrequited. In fact, a growing number of Kassner’s colleagues are increasingly being embraced by the very same art establishment that has fallen underneath Kassner’s brush. Two years ago, Creative Growth’s John Martin, a 54-year-old artist who has been with the organization for 30 years, sold 35 colorful cutout sculptures to Facebook. Martin’s work now hangs alongside established contemporary artists like Drew Bennett and David Choe in the tech giant’s massive new headquarters in Menlo Park, California. With other Creative Growth artists fetching top dollar from established collectors, this Oakland nonprofit rivals some of the country’s most reputable M.F.A. programs as an incubator and feeder for the global art market. In Creative Growth’s biggest coup yet, Dan Miller, the artist currently sitting at the Brother word processor, and the late Judith Scott are included in this year’s Venice Biennale, by far the most prestigious art show in the world.

“This really represents a huge advancement in how people appreciate and value the work of artists with disabilities,” says Tom Di Maria, the center’s high-energy director since 1999, who’s presently giving me a tour of the facilities. Di Maria tells me that he bristles when asked, often in hushed tones at art fairs, what’s “wrong” with his artists. “People push for it, but l say, ‘I don’t know. What’s wrong with you?’ We ended up in the Biennale because we haven’t led with disability or charity. We’ve led with high-quality art.”

The Central Pavilion at the 57th edition of the Venice Biennale is a world away from the Oakland garage where, in 1974, artist and educator Florence Ludins-Katz and her husband, psychologist Elias Katz, started Creative Growth with just a few tables and cans of paint. “It’s the classic entrepreneurial Bay Area story,” says Di Maria. “Think of all the companies founded in a garage that have gone on to affect culture.”

At the time, the couple was less interested in affecting culture than having an impact on the lives of the thousands of developmentally disabled Californians released from state institutions by the 1972 implementation of the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act. Although it was an outgrowth of the Independent Living Movement that sought to give the disabled equal rights, the LPSA effectively abandoned the disabled to poorly run and poorly funded county programs. Many experts agree that the act began what is known as the “institutional circuit,” whereby the disabled cycle through hospitalization, incarceration, and homelessness in endless revolutions of misery.

Elias Katz saw this unfold firsthand at the Sonoma State Home, where he worked. And since Florence Ludins-Katz taught art at both the high school and college levels, Creative Growth was the couple’s natural response. But it was more than just the Katzes that led to Creative Growth. Due credit must be given to the specific place and time of the art center’s founding: Oakland, 1974. To the immediate north was Berkeley and across the Bay was Haight-Ashbury, the political and creative centers, respectively, of the previous decade’s counterculture. As Lori Fogarty, the director of the Oakland Museum of Art, notes, “In Oakland in particular, there’s a long history of social justice work blending with artistic activity.”

By 1982, the Katzes had outgrown the garage and purchased the old auto body shop on what was then called Broadway’s Auto Row. It has been the organization’s home ever since. Just as the East Bay shaped Creative Growth, Creative Growth began to shape this little corner of the East Bay. Once a bustling commercial corridor full of car dealerships and auto repair shops, by the 1970s Oakland’s Auto Row was largely barren. This decline was partially a result of the white flight of the 1960s as well as to the interstate system, which not only served as the escape route to the suburbs but also lopped off Auto Row from the rest of Oakland. By the time Creative Growth moved in, the area was sufficiently fallow that a nonprofit with hardly any funding could buy a building. Even in 1999, when Di Maria joined, he remembers, “You had to jump in your car to go get a cup of coffee. There was nothing here.”

Di Maria bristles when asked what’s “wrong” with his artists. “I say, ‘I don’t know, what’s wrong with you?’”

Today, the blocks around Creative Growth are beehives of construction. In 2007, California Governor Jerry Brown, who was then the mayor of Oakland, introduced an initiative called the 10K Project to develop the neighborhood. According to Brown, if he could lure 10,000 people to settle in Downtown Oakland, the city would flourish. Ten years later, buildings continue to be constructed. There’s coffee now too. Around the corner from Creative Growth, at an art gallery and espresso bar called Tertulia, young professionals drink Stumptown coffee, savor artisanal doughnuts, and make use of the Wi-Fi. There are scores of other galleries in the neighborhood, like Transmission and Aggregate Space, and restaurants like Agave Uptown and new trendy eatery LocoL. Creative Growth, meanwhile, continues to be involved in the artistic ferment, as one of the founders of Art Murmur, a gallery crawl that draws nearly 10,000 people on the first Friday of every month. “It’s amazing to think that when Creative Growth first opened, there were no galleries in Downtown Oakland,” says Di Maria. “Art Murmur just shows how far we’ve come.”

But much as it has been in gentrified neighborhoods from Silver Lake in Los Angeles to Williamsburg in Brooklyn, “discovery” often means displacement—for both the marginalized communities that were historically there and the artists who helped spur the growth. “There are lots of people who are artists working two or three part-time jobs so they can pay this egregious rent,” says Ari Takata-Vasquez, owner of a small boutique in Oakland called Viscera, about the impact that tech money has had on the Oakland real estate market—which according to online database Zillow includes the five hottest neighborhoods in San Francisco’s metropolitan area. At Creative Growth, which employs 18 professional artists to help assist its members in technical matters, the shifts are felt.

“We’re okay because we own the building,” says Di Maria. “But many of our professional artists can’t afford to live in Oakland anymore. Many are faced with dislocation.” At this, Di Maria nods to Steve Oriolo, a studio instructor who works with Miller twice a week. Oriolo peers over Miller’s shoulder. “Does that say chandelier?” he asks. “Chandelier, right?” replies Miller, as he types the word for the hundredth time.

Meanwhile, Creative Growth’s mission is the same as it was in 1974: “To allow people with disabilities to grow and to be creative,” says Di Maria. “Importantly, the Katzes also hoped their people could eventually exhibit and sell their work to become professional artists.” With the inclusion of Miller’s work in the Biennale, says Di Maria, “Dan’s finally proving that artists with disabilities aren’t in the ghetto. They aren’t disenfranchised. They can be cultural leaders too.”

For original article, visit AmtrakTheNational.com.

Meet the Disabled Artists Creating a New Space for Talent in the Art World

Meet the Disabled Artists Creating a New Space for Talent in the Art World

The Artful Lodgers

The Artful Lodgers